Putting aside some of the floor covering depicted which look really like seldjuks rugs (design, borders, era) or rugs from a different origin, and others examples looking like textiles, I have another hypothesis one can apply to the remaining ones.

When looking at the following picture, one can remark details of the depicted floor covering:

Annunciation, Siena, ca. 1345, formerly in Schlossmuseum, Berlin

Annunciation, Siena, ca. 1345, formerly in Schlossmuseum, Berlin

Here the slit of the wall is prolonged on the ground

The tile hypothesis:

The inlaid tile was one of the great inventions of medieval craftsmen. Production of such tiles involved stamping the surface of an unfired slab of clay with a carved wooden block, impressing the design into the surface. The hollows were then filled with white clay.

The technique produced tiles that were both striking and durable, and had the particular advantage of being suited to mass production. Inlaid tiles, primarily used for floors, were made in quantity in England from the 13th to the 16th century.

Inlaid floor tiles (with decoration inlaid into their surface using contrasting coloured clay) were produced in England from at least 1237. During the 13th century they were used to decorate palaces and religious houses.

Ca.1280. This tile is a typical product of what is known as the Wessex School. This group of tilemakers was active in the later part of the 13th century, and produced tiles for a large number of sites throughout the region. Among these were the cathedrals of Salisbury and Winchester.

Ca.1280. This tile is a typical product of what is known as the Wessex School. This group of tilemakers was active in the later part of the 13th century, and produced tiles for a large number of sites throughout the region. Among these were the cathedrals of Salisbury and Winchester.

Ca.1270-1300. This 13th-century inlaid tile bears a double-headed eagle, the emblem of Henry III's brother, Richard of Cornwall. It was apparently found at a site in Lyme Regis. Tiles of the same design were used at Cleeve Abbey in Somerset, where a medieval tiled floor has survived almost intact at the site of the refectory. This heraldic design was among several first produced to commemorate the marriage in 1271 of Richard's son Edmund to Margaret de Clare.

Ca.1270-1300. This 13th-century inlaid tile bears a double-headed eagle, the emblem of Henry III's brother, Richard of Cornwall. It was apparently found at a site in Lyme Regis. Tiles of the same design were used at Cleeve Abbey in Somerset, where a medieval tiled floor has survived almost intact at the site of the refectory. This heraldic design was among several first produced to commemorate the marriage in 1271 of Richard's son Edmund to Margaret de Clare.

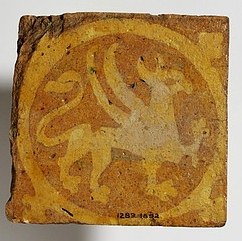

Ca.1250-1300. The griffin combines the wings and head of an eagle with the body of a lion. The main source of inspiration for the portrayal of creatures was the Bestiary, a collection of descriptions of beasts to which Christian and allegorical interpretations were added.

Ca.1250-1300. The griffin combines the wings and head of an eagle with the body of a lion. The main source of inspiration for the portrayal of creatures was the Bestiary, a collection of descriptions of beasts to which Christian and allegorical interpretations were added.

Similar tiles depicting griffins were used to decorate the floors of royal apartments at Clarendon Palace, Wiltshire. At Clarendon tiles featuring lions and griffins were used in pavement dated between 1250-1252. Designs established at Clarendon were repeated at sites throughout the south-west of England and South Wales

Ca;1250-1300. Red earthenware with an impressed design of a lion and infilled with white slip and covered with a clear lead glaze

Ca;1250-1300. Red earthenware with an impressed design of a lion and infilled with white slip and covered with a clear lead glaze.

Regards,

Y

Source: V&A Museum