HI all,

The many rugs with «small Holbein pattern» featured in Renaissance paintings are mostly attributed to Ottoman- / Anatolian- weavers and so are roughly 70 extant rugs and fragments of the type (1). In the essay, I hinted at a possible alternative main source: Timurid Persia, with later migration of the pattern to Anatolia and even to Spain (2) during the fifteenth- or sixteenth century.

In fact, among experts there are diverging opinions (what did you expect ?):

- Amy Briggs (3) using her exhaustive review of Timurid miniatures concluded that the «small Holbein pattern» was one of the most frequently used rug motifs during the Timurid rule of Persia.

-Christies‘ experts, among others, seem to share Briggs’ views: « The 'small pattern Holbein' design is one which is part of the international Timurid style. Amy Briggs in her seminal article clearly demonstrated the link between the 'small pattern Holbein' rugs and Timurid Persian arts » (4)

-Eleanor Simms, for example, disagrees: « The validity of using pictorial art as a source of evidence for textiles that no longer survive is,..., questionable at best ». (5)

In the following, SHR = Small Holbein Rug.

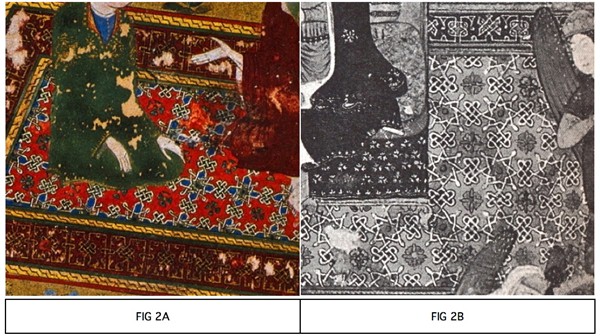

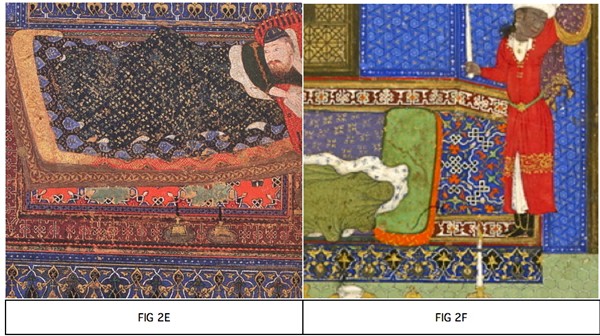

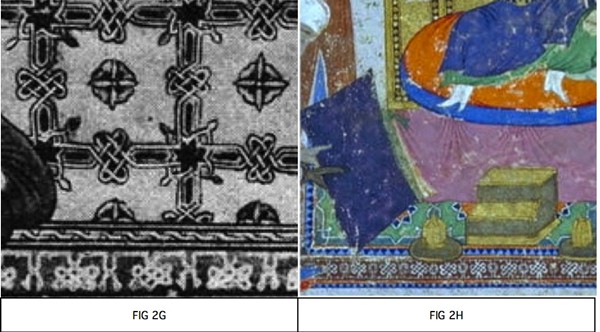

- Even a quite superficial survey of Timurid miniatures reveals a great number of SHRs. Far from being standardized, the pattern shows variations in details which suggest that real rugs were copied, not any academical standard. (FIG 1 and FIG 2.) Red and blue are often, but not always dominant field colors (green, as in FIG 2H.)

FIG 1. Timurid. 1429. Herat school. Baysungur in a garden. Detail .

FIG 2. Various Timurid « small Holbein» patterns

- SH is clearly the most frequently used rug field pattern illustrated by the painters of the Timurid Royal Libraries (kitabkhana). If one remembers that these Royal Libraries were an important tool for regime propaganda for all Persian dynasties (6), (as were the royal rug factories), one can perhaps assume that the rugs featured in the miniatures were not picked at random, but rather supposed to make a statement.

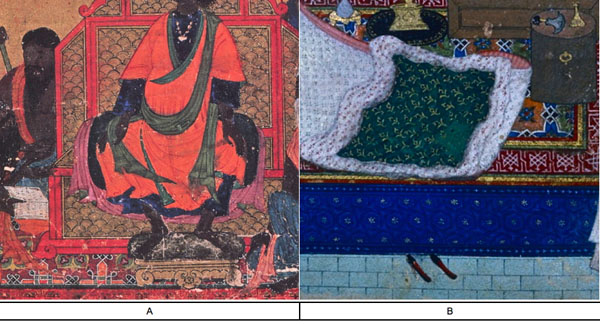

- A couple of SHRs are found in even older Persian miniatures, dating from the Il-khanid period and from the period immediately preceding the Timurid Empire. This indicates that the SH pattern was known and used in Persia before the founding of the Timurid Empire (and well before the creation of the Ottoman empire in Anatolia, by the way).

FIG 3: Pre-Timurid «small Holbein rugs»

- According to J. Mills (7) the first SHR in European painting dates from 1451 and the bulk of them were painted between 1451 and 1550. Thus, many miniatures featuring SHRs pre-date their first representations by European masters by 40-75 years.

- One of the characteristics shared by extant SHRs, those illustrated in Timurid miniatures and in European paintings, is the ubiquity of the kufic border.

Although kufic borders appear in some para-Mamluk rugs and in a limited number of Anatolian- or Spanish fifteen- and sixteenth century rugs featuring other field motifs as well, they are

extremely frequent in illustrations of Timurid rugs, independently of the field motif. IMHO one could perhaps even consider that a kufic border in a (15th-16th century-) SHR is a strong presumption of Persian- (Timurid-) rather than Anatolian- (Ottoman-) origin.

- Even if the reader accepts to walk with me on that thin ice, agreeing that the earliest SHRs with kufic borders may indeed have been woven in Persia and not in Anatolia, he would probably mention the fact that the roughly 70 extant SHRs (including fragments) surely must have been woven with

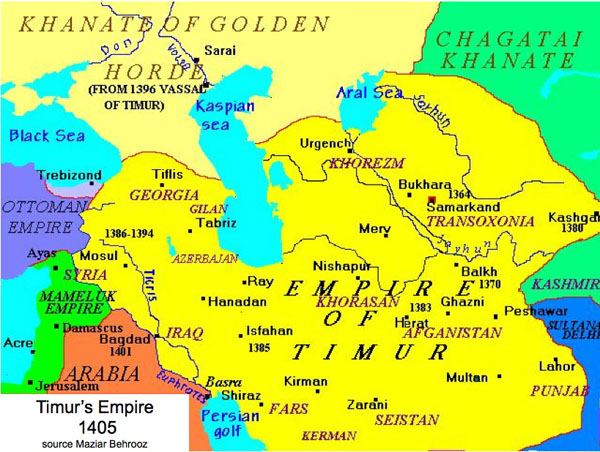

symmetrical knot, since so many experts attribute them to Anatolia. To competently discuss this fine point there are much more knowledgeable people than me here on Turkotek, but I was under the (mistaken?) impression that, even though classical Persian workshop-rugs were woven with asymmetrical knots at least since the Safavid period, there are, still today, several Persian clans and tribes which use prevalently the symmetrical knot (the Luri for example?). One could also mention that Timurid Greater Persia included regions which (today) use mainly the symmetrical knot, in particular in the Northwestern area of the former Empire. Since we know only one rug fragment tentatively attributed to the Timurid period, what proof do we have that Persian Timurid rugs were not, at least in part, woven with a symmetrical knot too?

FIG 4. Map of major extension of Timurid Persia

If the possibility of a Persian origin for the SHR rugs is accepted, one can walk a little bit further on this thin ice and look for a credible cradle inside Persia. I would propose two options, which both respect the main characteristic of Rugdom Science (A total lack of proof

).

A:Timur’s clan fiefdom: The founder of the dynasty was a prominent Barlas tribesman, a Turco-mongol clan (more Turkik than Mongol) established in Transoxiana, around Kish, southwest of Timur’s capital Samarkand, towards the Amu-darya. The base for my fragile theory would be that Timur might have imposed to his kitabkhana painters to feature his clan’s traditional rugs (or alternatively that the painters did it to flatter the boss and his clan). Martin, in a recent thread about kufic borders, made a fascinating remark, noting that the field-patterns of Timurid SHRs show interesting analogies with some extant Turkmen khali. Could the fifteenth-century Turkmen (who already lived nearby in the trans-Caspian area, at the time) have been influenced by their powerful southeastern neighbors (and nominal suzerains) and copied / interpreted their rugs?

or

B: The northwestern part of the Timurid Empire: In this area, still today, the symmetrical knot is sometimes in use. This area includes Tabriz, at the time an important city, which together with Herat was home of the most important Timurid kitabkhana. Perhaps the painters reproduced the best rugs they saw in the Tabriz bazaars or in the elite’s homes? One weak point in this theory is that many miniatures featuring a SHR are attributed to the Herat kitabkhana too. A fact which rather supports option a). On the other hand the few SHRs illustrated in pre-Timurid miniatures (FIG 3) are attributed to the Tabriz school. A point in favor of option b).

Litterature

1) According to Charles Grant Ellis, cited in Christies’ catalog, May 2003.

2) At least one fifteenth-century extant SHR (today in Boston museum) was woven with Spanish knot.

3) A. Briggs. Timurid Carpets I: Geometric Carpets, Ars Islamica 7, 1940, pp.20-54. Mrs Briggs’ publications are extremely difficult to find today. She is cited by many authors, but I wonder how many of them really own a copy. I don’t.

4) Christies. May 2003

5) E. Simms. Encyclopedia Iranica. Carpets viii. The Il-khanid and Timurid Periods. Vol. IV, Fasc. 7, pp. 864-866. Mrs Simms is surely right when she cautions us not to believe that rugs illustrated in Timurid miniatures were exact reproductions of the real thing. In fact, the colors of the miniatures were dictated by the nature of the mineral pigments used , which were mostly much brighter than whatever can be done with natural wool dyes. (Especially the reds, the blues and the gold-yellows). However, these rug illustrations also show a remarkable consistency of design, (with enough little variations to suggest a real model), both in the field patterns and in the systematical choice of a kufic border (About four different kufic «scripts» are met).

6) The Princely vision, Persian Art and Culture in the fifteenth century pp. 32-50, «.... From the earliest periods, Muslim powers united political activity with an interest in books. Accordingly it was the staff of the kitabkhana, painters and calligraphers in particular, who were charged with visualizing princely aspirations and affirming ruler’s legitimacy and power....» . Timur and his immediate successors were particularly aware of the importance of regime propaganda by means of spectacular architecture, lavishly illustrated manuscripts and rich artifacts, certainly including rugs. Later, the Safavid Shahs, especially Shah Abbas, shared this opinion. The latter is said to have personally influenced the design of rugs woven in his royal factories.

7) John Mills, 'Small Pattern Holbein Carpets in Western Paintings', Hali, vol.1, no.4, pp.326-330

_____

Illustrations:

FIG1: 1429. Timurid. Herat school. Baysungur in a garden. Detail .

FIG 2A: 1425. Timurid. Herat school. Poet Sa'di and friend. Detail. Chester Beatty Lib. Dublin

FIG 2B: 1427-1428. Timurid. Herat school. Humay in palace of fairies. Detail. Vienna Nationalbibliothek

FIG 2C: 1427. Timurid. Herat School. Drunken prince and maiden. Detail. Chester Beatty Lib. Dublin

FIG 2D: 1427. Timurid. Herat school. Princes playing games. Detail. Berenson collection.

FIG 2E: 1434-1440. Timurid. Herat school. Tahmina enters Rustam’s chamber. Detail.

FIG 2F: 1444. Timurid. Herat school. Firdawsi's Shahnameh. Detail. Royal Asiatic Soc. London

FIG 2G: 1450-1470. Timurid. Herat school. Detail

FIG 2H: 1469-1470. Timurid. Jamshid instructs his people. Detail. Chester Beatty Library

FIG 3A: 1330-1340. Il-khanid. Tabriz school. The Indians. From a "kalila wa dimna". Detail. Istanbul

FIG 3B: 1370-1375. Chubanid. Tabriz school. Cobbler cuts the nose of barber’s wife. Detail. Topkapi. Istanbul