Hi

there had been tension between the Ottoman and the Safavid for decades. The latter intermingled in the succession process of the former, recruited among the Turkmen in parts of East Anatolia the Ottomans claimed their dominion – and from a Sunni Ottoman perspective, the Safavids were heretics. When the hour came on 23rg August 1514 it struck disaster to the Safavids. By the skin of a tooth Shah Ismail escaped alive but was wounded. This jeopardized his position lastingly, as he was not only secular leader but was also considered the invincible Mahdi, the returned 12th Imam by his followers. The Ottomans took Tabris, pillaged it and shuffled Ismails Harem to Istanbul. It was later returned in a somewhat ruffled state, as the saying has it. About this it seems, Ismail fell depressed and took up drinking. Key artisans were shipped to Istanbul for good, so the famous Tabris metal workers (Newman 2006).

Iran’s Anatolian and Mesopotamian provinces were lost to the Ottomans in the process. They had been an integral part of the empire since the days of Cyrus the Great (558-530 BC). Warfare between the stated continued for another almost 50 years until the settlement at Amasya in 1555.

But this did not mean peace, not to the population anyway. In Eastern Anatolia, overstressed structures after the collapse of the Ilkhanate gave in further, economical and cultural decline set in, religious persecution too resulting in large scale emigration and resettlement. The Jelali revolts were a symptom of it. Daily life had become severely disrupted. The bright lights of the capital and court at Tabris vanished behind the horizon, first to Quazvin, then to Isfahan. In the other direction too, resources were drawn to the west; a proverbial saying that goes like this was still heard in the east in the 1970s, not without bitterness: anything precious in the east finds its price in Istanbul. So did the rugs, and their workshops and the resettled weavers, they assimilated in the west and sooner or later new designs emerged. Far Eastern Anatolia (give and take a little all area east of Euphrates) was forsaken; as the creative cradle of rug designs that it once was, it had stopped rocketing long ago, when eventually the focus of foreign rug experts fell on a tradition, that was now primarily associated with Western Anatolia. However, the tradition was continued in far Eastern Anatolia, NW Iran and neighbouring areas as well, among the wandering tribes and in villages almost up to the present day. The produce was nice enough (‘collectible’) but it seemed to be a humble reflection of the great ‘classical’ rugs identified in the west and therefore was regarded as minor copies of them according to the well known formula of designs being ‘handed down from court to village’ – in my theory, it is the humbler floors within the ancient empires in tents and villages on which the designs flourished probably since times immemorial, for every know and then one being elevated to a degree of highest refinement.

In 2007 at the Volkmann-Treffen in Berlin, Michael Franses lectured on the ‘Star-Variant’ of West-Anatolian Ushak design carpets. He gave a complete and thorough overview, and in his conclusion had to concede: ”As I have stated before, when studying carpets, certain assumptions have to be made that are not provable. We do not know the circumstances under which the rugs were woven, nor do we know how the patterns were conceived or how they evolved. We do not know how the patterns of one ‘atelier’ influenced another, nor whether the weavers wove for themselves or made their carpets for sale. We assume that a cottage industry expanded with the increase in demand from Western Europe and that small ‘ateliers’ were financed by merchants. No evidence has thus far been discovered to link specific weavers or workshops to surviving carpets, none (of) which are either signed or dated. Indeed the only indication of their age is that some Ushak carpets have been depicted in Western paintings. But the artist may have been copying a rug seen in an older painting, so the rug depicted might be older than the painting we are looking at. On the other hand, the actual rug that we may wish to compare with one illustrated in a painting may be a much more recent version.”

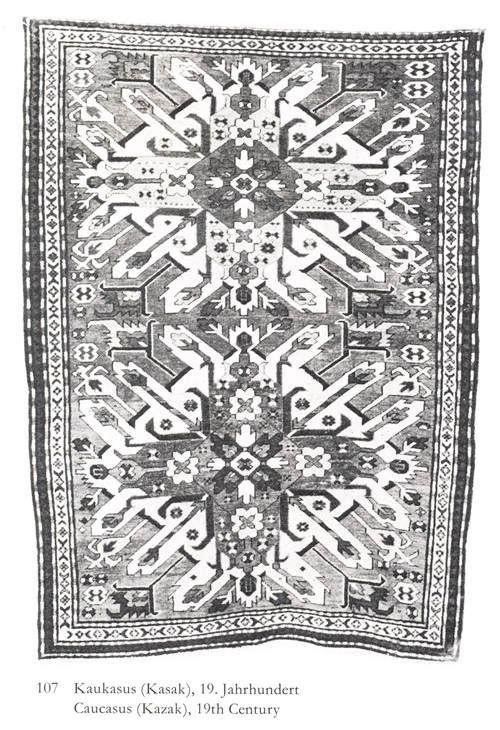

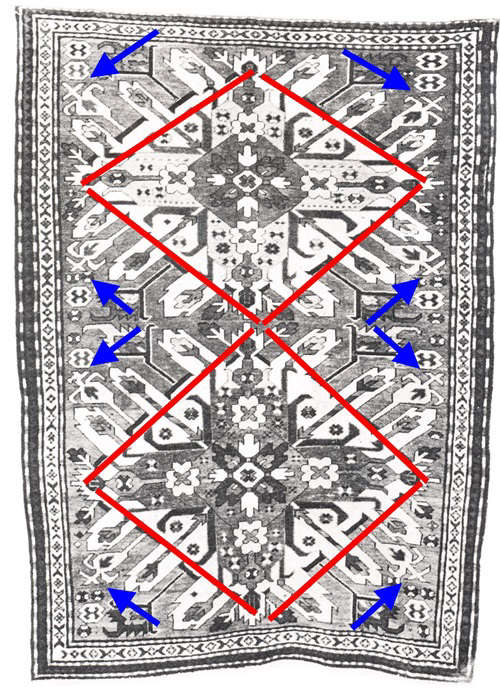

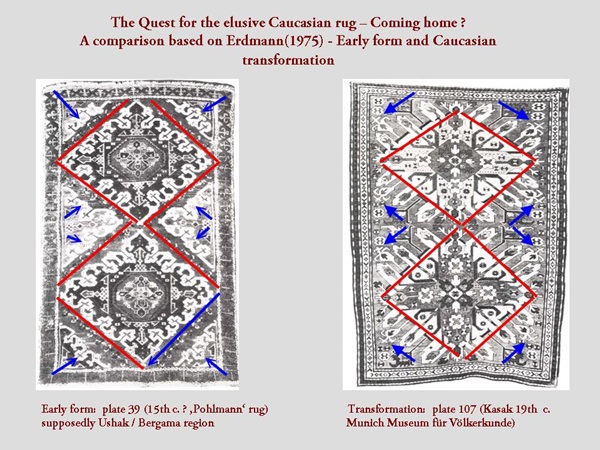

I greatly admire Michael Franses for his knowledge and experience, his matter-of-fact style of presenting, the honesty and transparency with which he names gaps in the collective knowledge. It seems reasonable to put forward in steps a different view, which may lead to a theory with fewer assumptions. In the given case this means attributing the Pohlmann / Scheunemann rug to Azerbaijan instead of Western Anatolia and establishing its ancestry in relation to a well known later group of rugs, as part of the ‘Quest for the elusive Caucasian Rug’ started by Pierre, the Caucasian ‘Eagle’ or ‘Sunburst’ type:

Regards,

Horst